Preface

There was no post last week because the holiday season/master’s thesis finishing season/parental pet care season is in full swing, and I’ve been completely crushed. This week isn’t easy either, but I didn’t want to leave you empty-handed when there’s so much to talk about!

This time I wanted to present you with another installment in the shiny tricks series. I’m going to show something that isn’t quite as ‘tricky’ but can still be non-obvious to those who don’t use reactivity and environments proficiently. I will tell you about factories of reactives. And the tale starts with an example.

Basic example

Remark: As I often use the shiny::reactive() function in this article, it will probably not have escaped you that I always wrap the first argument of this function in curly brackets. By doing so, I make it clear that the function’s argument is an expression, not its value. Most of the time, this is not necessary, but it is a habit of mine and helps me keep the code readable.

Suppose we have an application that accepts several numeric inputs that perform very complex transformations, then plots and outputs the result. Let’s start with an example with two inputs.

library(shiny)

ui <- fluidPage(

sidebarLayout(

sidebarPanel(

numericInput("a", "input a", 1, 0, 100, 1),

numericInput("b", "input b", 1, 0, 100, 1)

),

mainPanel(

textOutput("text_a_b"),

plotOutput("plot_a_b")

)

)

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

temp_val <- reactive({

c(

input[["a"]] + input[["b"]],

input[["a"]]^3 * input[["b"]],

27 - (input[["b"]] + input[["a"]])

)

})

output[["text_a_b"]] <- renderText(

paste(temp_val(), collapse = " -- ")

)

output[["plot_a_b"]] <- renderPlot(

plot(temp_val(), temp_val())

)

}

shinyApp(ui, server)

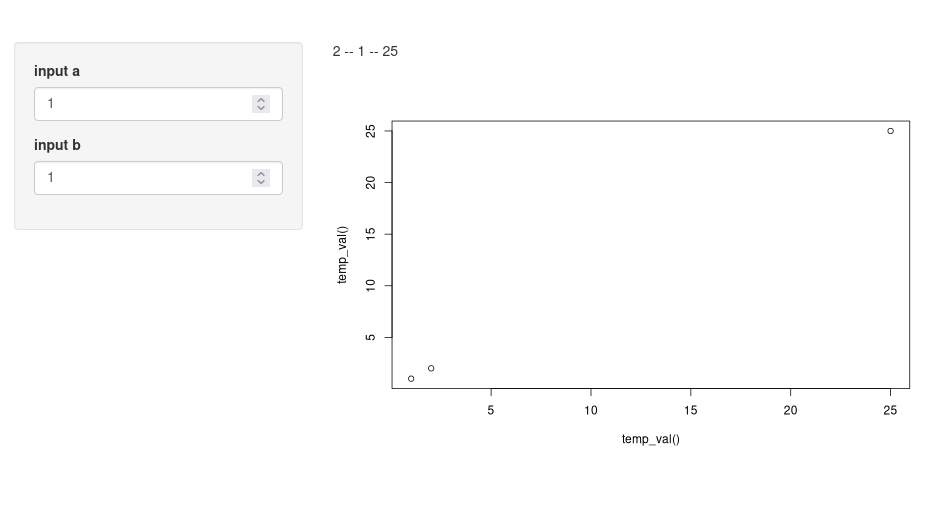

Basic example app.

This application takes two inputs and performs an incredibly complex calculation that, in effect, returns a three-element vector. This vector, an intermediate value, is later used for the two outputs.

Of course, again, the calculations themselves, the inputs and outputs, are not relevant or even meaningful here. It’s just my usual problem finding simple examples to demonstrate not-so-simple concepts. The only important thing is a reactive intermediate value calculated from inputs.

So far, nothing complicated. So let’s add a little spice.

ui <- fluidPage(

sidebarLayout(

sidebarPanel(

numericInput("a", "input a", 1, 0, 100, 1),

numericInput("b", "input b", 1, 0, 100, 1),

numericInput("c", "input c", 1, 0, 100, 1),

numericInput("d", "input d", 1, 0, 100, 1),

numericInput("e", "input e", 1, 0, 100, 1)

),

mainPanel(

textOutput("text_a_b"),

plotOutput("plot_a_b"),

plotOutput("plot_b_d"),

tableOutput("table_c_d"),

textOutput("table_a_e")

)

)

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

temp_val_1 <- reactive({

c(

input[["a"]] + input[["b"]],

input[["a"]]^3 * input[["b"]],

27 - (input[["b"]] + input[["a"]])

)

})

temp_val_2 <- reactive({

c(

input[["b"]] + input[["d"]],

input[["b"]]^2 * input[["d"]],

8 - (input[["d"]] + input[["b"]])

)

})

temp_val_3 <- reactive({

c(

input[["c"]] + input[["d"]],

input[["c"]] * input[["d"]],

1 - (input[["d"]] + input[["c"]])

)

})

temp_val_4 <- reactive({

c(

input[["a"]] + input[["e"]],

input[["a"]]^4 * input[["e"]],

64 - (input[["e"]] + input[["a"]])

)

})

output[["text_a_b"]] <- renderText(

paste(temp_val_1(), collapse = " -- ")

)

output[["plot_a_b"]] <- renderPlot(

plot(temp_val_1(), temp_val_1())

)

output[["plot_b_d"]] <- renderPlot(

plot(c(1, 1, 1), temp_val_2())

)

output[["table_c_d"]] <- renderTable(

data.frame(x = temp_val_3(), e = exp(temp_val_3()))

)

output[["table_a_e"]] <- renderText(temp_val_4())

}I modified the UI and the server to do more things. Everything is centered around the very complex transformation as before, but we have more inputs, more outputs, and more temporary values. And above all: more iterations. As you may have already realized, I’m a prominent opponent of repetition in code: if there’s copy-paste somewhere, it can probably be done better. And that’s what we’re going to try to address. This code has two primary repeating rhythms: inputs and the calculation of temporary values. We can fix the first repetition very quickly, and I’ve already done similar things in the last part of the article series, so I won’t go into it this time. Let’s deal with the more exciting thing, which is the server-side repetitions.

Solution 1: wrap a function with a reactive.

The thing that jumps to mind almost immediately is the creation of a function that generates these temporary values.

magic_func <- function(name_1, name_2, param) c(

name_1 + name_2,

name_1^param * name_2,

param^3 - (name_2 + name_1)

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

temp_val_1 <- reactive({ magic_func(input[["a"]], input[["b"]], 3) })

temp_val_2 <- reactive({ magic_func(input[["b"]], input[["d"]], 2) })

temp_val_3 <- reactive({ magic_func(input[["c"]], input[["d"]], 1) })

temp_val_4 <- reactive({ magic_func(input[["a"]], input[["e"]], 4) })

# here, put the other part of the server code...

}This already looks much, much better! It’s more readable and less error-proof, so the advantages alone. And that’s basically where we could leave it. But if it satisfied us, we wouldn’t read any further.

Solution 2a and 2b: extract input.

Another thing that we can improve in this solution is to refer to the input object every time there are multiple arguments to the magic_func() function. So maybe we can move this reference inside the function?

magic_func <- function(name_1, name_2, param) c(

input[[name_1]] + input[[name_2]],

input[[name_1]]^param * input[[name_2]],

param^3 - (input[[name_2]] + input[[name_1]])

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

temp_val_1 <- reactive({ magic_func("a", "b", 3) })

temp_val_2 <- reactive({ magic_func("b", "d", 2) })

temp_val_3 <- reactive({ magic_func("c", "d", 1) })

temp_val_4 <- reactive({ magic_func("a", "e", 4) })

# here, put the other part of the server code...

}

Output error message.

Unfortunately, we will find that this is not enough. The input object is for the interior of the function unknown. That may seem unnatural if you understand the basics of how scopes work in R – if the object is not found in the current environment, the parent environment is checked (I talked about this in the last part of the series, I refer you to it again). Here, however, this situation is not so evident because the server environment is not in the search path of the environment in which the function is defined.

That can be resolved in two ways: either move the function definition inside the server or pass an input object as an additional parameter to the function. I leave the proof to the reader.

Solution 3: wrap a reactive with a function (factory).

However, we could go even further and reduce code redundancy. And this is where we want to create a reactive factory.

What is a factory of reactives? It is simply a function that creates a reactive. Every shiny user should be familiar with the primary function used to create and register reactives – namely, shiny::reactive().

But this is the most general factory that exists – you pass it any expression, turning it into a reactive expression. We would like to have something more concrete, i.e. instead of writing reactive({ fun(parameters) }) writing reactive_fun(parameters).

In our case, we want to replace

reactive({ magic_func("a", "b", 3) })with

r_magic_func("a", "b", 3)Notice the r_ I added to the function name. Suggesting that this function returns a reactive is a good idea.

So, let’s try to make such a function!

r_magic_func <- function(name_1, name_2, param) reactive({

c(

input[[name_1]] + input[[name_2]],

input[[name_1]]^param * input[[name_2]],

param^3 - (input[[name_2]] + input[[name_1]])

)

})Does it work? Yes… at least: almost. It will not work unless we consider our previous solution’s experiences: it needs to be either defined in the server function or take input as a separate parameter.

But what if we do not want to do either of those? We are lazy and do not want to type all the parameters that will look the same either way. Those “inputs” typed every time are annoying, but if, in addition, we have some other reactive values that we would have to pass on each time, this would be very annoying. On the other hand, defining functions within a server works for small apps but is terrible if you have an extensive, packaged application that wants to keep its code tidy and test its functions with unit tests. So how do we get around these obstacles?

reactive has additional parameters that are worth looking at. Of particular interest to us is the env parameter. It indicates the environment in which the expression passed as the first parameter should be evaluated. That is usually set as the environment calling the reactive function. So this is the reason why our original factory is not able to see the input object – it is not in the environment calling the reactive. So what happens if we replace this environment with the environment which calls our factory function?

r_magic_func <- function(name_1, name_2, param) reactive({

c(

input[[name_1]] + input[[name_2]],

input[[name_1]]^param * input[[name_2]],

param^3 - (input[[name_2]] + input[[name_1]])

)

}, env = rlang::caller_env())

We got a different error! That’s progress!

Why are we getting this error this time? Since we replaced the evaluation environment with the caller environment, it can see all objects available in the server environment. Still, it cannot see the objects available inside the r_magic_func – namely, name_1 (pun intended) and other parameters.

Our favorite package comes to our rescue: rlang! We can use a similar idea with an injection of values just as in the previous tutorial.

r_magic_func <- function(name_1, name_2, param) rlang::inject({

reactive({

c(

input[[!!name_1]] + input[[!!name_2]],

input[[!!name_1]]^(!!param) * input[[!!name_2]],

(!!param)^3 - (input[[!!name_2]] + input[[!!name_1]])

)

}, env = rlang::caller_env())

})And it fulfills all of our objectives! One more thing to do: if we want to take care of the r_magic_func, we should ensure that this factory can also be called within other functions. So, instead of fixing the env parameter of reactive as the rlang::caller_env(), we should make it a default parameter of r_magic_func, similarly to reactive itself does it.

Discussion & summary

My example will probably seem too artificial and contrived to some of you. I am not writing this for the sake of the brilliance of the example but rather to teach the concept behind it. Probably many of you will find a suitable application for this method. Some may agitate that hiding the reactive behind a function is superfluous, but, in my opinion, it is just another step towards code readability. This kind of factory can be further generalized and improved, which I will discuss next time.

One more thing: modules. I still deliberately avoid using modules. What I am doing here could also be done using modules, although I think it is much less intuitive than in the last part of the series. I will also write about modules another time (ah, too many of these topics!).

I have shown you how to use tools to change the evaluation environment to control code execution and, as a result, reduce unnecessary repetitions. This is only the second step on the long road to becoming a master at using the language to its full potential. If you have any questions or comments, contact us on Twitter or make an issue on Github.